Heraldry is a science, art and craft whose origins can be traced back to the late 11th century, at the dawn of the Middle Ages. It has been defined by one expert as “a system of hereditary devices centered on the shield.” What is striking about heraldry is its endurance and its adaptability. Although the factors that led to its creation and expansion no longer operate, it is still with us; and new heraldry is still being created.

Heraldry is a science, art and craft whose origins can be traced back to the late 11th century, at the dawn of the Middle Ages. It has been defined by one expert as “a system of hereditary devices centered on the shield.” What is striking about heraldry is its endurance and its adaptability. Although the factors that led to its creation and expansion no longer operate, it is still with us; and new heraldry is still being created.

The idea of adorning shields with emblems or symbols pre-dates the time of heraldry. There is pictorial evidence, dating back to ancient history, of warriors displaying symbols on their shields to identify themselves. What is distinct about heraldry is that it is hereditary: the particular arrangement on an individual’s shield – an arrangement constituting the “coat of arms” – is unique and descends to his posterity forever.

Heraldry was first used by monarchs and great magnates but progressively was adopted by lesser nobles and knights, and eventually by institutions and non-combatants such as churchmen and women (who are not supposed to engage in combat). But while it might appear that coats of arms are the exclusive province of royalty and nobility, in fact it was established early on in legal treatises, notably by Bartolo di Sassoferrato, that any man may assume arms of his own making so long as they do not imitate another’s. The same legal scholars do however distinguish between arms that are assumed (self-granted) and those that are granted by a ruler. The granted arms are held to be superior to the assumed ones; but all are equally valid. In fact many centuries-old European arms are those of burghers and peasants.

At its peak, ca. 1400, heraldry was one of the most visible manifestations of feudalism, a complex system of obligations linking vassal to suzerain, connecting a knight to a king. All were armigerous – that is, all bore heraldic arms. But by the 1500s that structure was unraveling. With feudal monarchies slowly starting to evolve into modern centralized states, vassals were replaced with standing armies; while emerging middle classes began to compete with and acquire the rank of the “old” noble ruling classes. As a result heraldry, far from disappearing, was appropriated by “new” families as a sign that they had arrived. From the 1600s to the 1800s heraldry enjoyed a new phase as a kind of validating public status symbol.

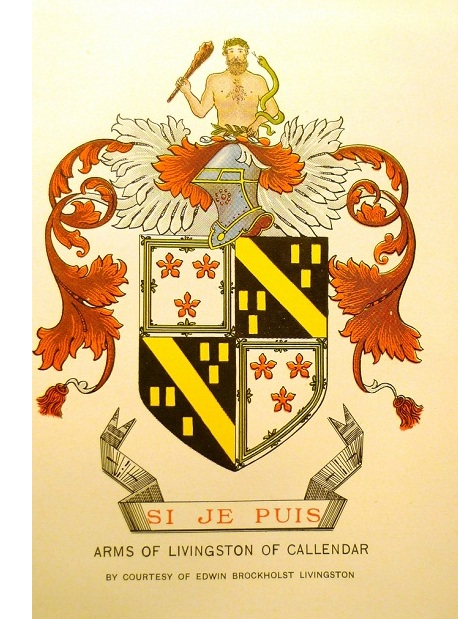

Today heraldry is more or less accessible to all. As noted above, anyone may assume arms. Under certain conditions, others may apply to a heraldic authority – such as the College of Arms in London or the Lyon Court in Edinburgh – for a grant of armorial bearings, which includes a shield, crest, helm and mantling. A coat of arms from such a body is considered to be personal property that conveys no legal privileges. Its greatest value is personal in that it is an expression of identity and achievement for the grantee.

Heraldric Design

Heraldry is remarkably adaptable and can be perpetually reinterpreted. It is adaptable in that new objects, formations or patterns may be incorporated into shields today and will be in the future. Furthermore, there is always room for reinterpretation of heraldic design. It is mistakenly thought by many that a coat of arms, once granted and depicted for the first time, can only ever be depicted in that same manner, or copied. But that is not the case. Heraldry is actually described in words – the language is called “blazon” and is clearly of French derivation. The words describe the shield – its color(s) and the objects or charges upon it. It is up to the heraldic artist – a painter, sculptor or metal worker – to understand those words and create a rendering of them. Thus heraldic compositions can always be refreshed and updated with time and changing fashion.

A good heraldic artist is vital to make heraldry seem vibrant and attractive, versus dull and uninteresting. These artists operate in a special sphere between graphic design, commercial art and draughtsman ship. It takes a particular talent to render animals heraldically, for example: they are stylized creatures, not lifelike but also not cartoons. Equally, the shape of the shield (wide top, narrow base) requires a capacity to understand scale and proportion so that the charges look balanced and the shield full but not crowded. There are computer programs available today that facilitate the creation of heraldic renderings but they have a mechanical feel and lack an artistic touch.

During its long evolution, heraldry in different nations has taken on local characteristics or styles with the result that it is often possible to tell where a coat of arms comes from. But not always since it has happened different families in different places have almost identical arms, especially very old ones from a time when designs were simple. And even in the same country it could happen that two people claimed the same arms. But only one could bear them as his own, so the other would have to yield to a judgment.

Links to Heraldic Resources

- The College of Arms

- The Court of Lord Lyon

- The Canadian Heraldic Authority

- The Heraldry Society of England

- The Heraldry Society of Scotland

- The White Lion Society

- The Society of Heraldic Arts

- The Institute of Heraldry

- The Chief Herald of Ireland

- The Royal Heraldry Society of Canada

by John Shannon, Chairman, NYG&B Heraldry Committee; President, The College of Arms Foundation.

April 2011

© 2011 The New York Genealogical and Biographical Society

All rights reserved