The phenomenon of orphan trains is a fascinating and upsetting aspect of New York’s history which has captured the imagination of genealogists and popular culture alike.

From 1854 to 1929, hundreds of thousands of abandoned and orphaned children were sent from east coast cities to the American countryside in a “placing out” effort to find them loving homes.1

The movement boasted an impressive success rate by relocating over 250,000 children to midwestern states. The genealogical implications of the largest children’s migration in history are both obvious and enormous. With an estimated 2 million descendants alive today, orphan trains are critical to the family histories of so many Americans from coast to coast.

Continue reading for helpful tips, records, and links for researching orphan trains.

Origins of orphan trains

The influx of immigrants into east coast cities in the 1830s led to a tremendous rise in child homelessness, particularly in New York City. Its streets were home to an estimated 10,000 to 30,000 children in 1850.2 Nicknamed “street Arabs” for their wandering habits, these youngsters moved in gangs for protection and often sold matches, rags, and newspapers to survive.3 This prompted a rise of institutional orphanages, but minimal food, education, and attention were provided to residents who were expected to leave and fend for themselves by age 14.4

When a young minister and Yale graduate named Charles Loring Brace moved to New York for seminary training in the 1850s, he was shocked by his constant encounters with homeless youths. In a diary entry he recalled, “When a child of the streets stands before you in rags, with a tear-stained face, you cannot easily forget him. And yet, you are perplexed what to do.”5 Inspired by “placing out” programs in European cities, Brace was compelled to found the Children’s Aid Society with the mission of sending as many vagrant youths out west to the countryside as possible.6

The children selected for the program were those deemed most likely to be successfully placed in new homes. This meant they were mostly white and of the same Western European background as prospective Midwestern families. Attempts were also made to match native languages of children and families.7 As a consequence, non-white, disabled, and older children were generally excluded from the movement.

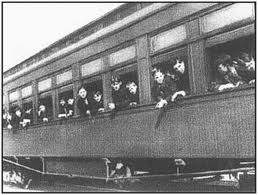

Most of the orphan trains leaving from New York City originated at Grand Central Station. On the day of departure, the children were dressed in new clothing and oftentimes not told where they were going or why. While some were already assigned families, others would be displayed at stops along the way in an auction-like event. In the days leading up to arrival, fliers and local newspapers along the train’s route advertised adoptable children.8

Via Wikipedia.

Orphan train successes

Despite its obvious controversies, the orphan train process was in many ways a success. Countless new families were formed. A loving adoptive father holding his new baby at the train station told a Nebraska newspaper, “It beats the stork all hollow. We asked for a boy of 18 months with brown hair and blue eyes, and the bill’s filled to the last specification. The young rascal even has by name tacked on him.”9

Many such children flourished. Andrew Burke and John Brady, respectively governors of North Dakota and Alaska, rode orphan trains as children.10 In fact, the model was so successful that numerous orphanages partnered with the Children’s Aid Society in New York, Boston, Philadelphia, and Chicago.11 Other organizations, such as the Foundling Hospital of New York City, exported the model as well.

Orphan train problems

On the other hand, there were obvious drawbacks to the orphan train complex. The auction-like spectacle that took place at train stops was oftentimes degrading. Children were sized up and inspected in a fashion more appropriate for livestock than human beings.

So-called “train children” were frequently bullied and ostracized in their new communities. Some were rejected and never found a home. Others were mistreated by adoptive families or misused as free farm labor, leading to many instances of runaways.12 Ultimately, the implementation of child labor laws along with the rise of the welfare system in the 1930s led to the end of the orphan train complex, but its legacy is still felt throughout much of the country today.13

Researching orphan trains

Family history research related to orphan trains is very complicated. Oftentimes the origins of these children are shrouded in mystery. Due to stigma surrounding adoption, many orphan train passengers were never even told about their histories, and many were too young to ever recall where they came from. Older children were also strongly encouraged to break all contact with the past upon arrival in their new homes.14

To further the confusion, oftentimes records are just as scarce as oral histories. Lack of a standardized recording system and sheer numbers of orphans means that many migrations are unrecorded. Errors in name, religion, and nationalities were also not uncommon as many parents were non-English speakers or illiterate. To make matters even more complicated, many children were simply taken from the streets, so family origins were nearly impossible to gather.15

National Orphan Train Records Online

Although anyone researching the orphan train will undoubtedly encounter some of these roadblocks, there are many organizations and resources to help genealogists break through these brick walls. While some relevant records can only be accessed in-person, there are numerous online resources for family historians to explore. Below are five key links to get you started:

The National Orphan Train Complex Museum and Research Center located in Concordia, Kansas is a tremendous resource with many records, resources, and research guides.

The New York Foundling Hospital holds many records which often include birth family names for children originating in New York. These records can be accessed at the New-York Historical Society, which offers an online finding aid: Guide to the Records of the New York Foundling Hospital 1869-2009.

The Children’s Aid Society also holds records which in some cases list birth family names for children departing from New York. These records can be found at the New-York Historical Society, which has produced an online finding aid: Guide to the Victor Remer Historical Archives of the Children's Aid Society 1836-2006 (bulk 1853-1947)

Though not specifically related to orphan trains, New York Municipal Archives has put valuable birth and almshouse records online.

Footnotes

1. National Orphan Train Complex, "FAQs" National Orphan Train Complex. Accessed 1 October 2020. | ^Back to text

2. Andrea Warren, "The Orphan Train" The Washington Post. Accessed 1 October 2020. | ^Back to text

3. PBS, "The Orphan Trains" The American Experience. Accessed 1 October 2020. | ^Back to text

4. Warren, "The Orphan Train." | ^Back to text

5. PBS, "The Orphan Trains." | ^Back to text

6. Warren, "The Orphan Train." | ^Back to text

7. ibid. | ^Back to text

8. ibid. | ^Back to text

9. ibid. | ^Back to text

10. PBS, "The Orphan Trains." | ^Back to text

11. National Orphan Train Complex, "FAQs" | ^Back to text

12. PBS, "The Orphan Trains." | ^Back to text

13. Warren, "The Orphan Train." | ^Back to text

14. National Orphan Train Complex, "FAQs" | ^Back to text

15. ibid. | ^Back to text