The purpose of this article is to explore the plethora of information that may be just a letter away at the Department of Justice, Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS), if a family member was an alien residing in the United States in 1940 or later. The example given here is that of William Stevens, my grandfather. I obtained his Alien File (or A-file) by filling out a standard G-639 Form, downloadable from the INS website. Public access to these files is permitted under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA).

William Stevens was born on 30 September 1882, in Enfield, Middlesex, England, to William Stevens and Sarah Jane Platt.[1] Oral history has it that he joined the British Royal Navy at age 14 to obtain further schooling, not otherwise available to him at the time. After he made several attempts to escape the Navy, his parents purchased his way out, as he was still only 17. He later married a woman named Frances and had a daughter named Ida. They all moved to a place called “The Whiteway Colony,” near Stroud, Gloucestershire, where they lived for several years. During the First World War William Stevens obtained conscientious objector status and spent the early part of the war helping others to sneak out of the country to Ireland. Before the war was over, he immigrated to the United States, first arriving at the Port of New York on 9 October 1917 aboard the S.S. Pannonia.[2] He found his way to the Stelton Colony in Piscataway, Middlesex County, New Jersey, where he was enumerated in the 1920 U.S. Census.[3] This is where he met my grandmother, Clara Druss, who was married to Sigmund Brodsky.[4] Clara and William ran off to Noyac, Suffolk County, New York, where they had a son. They then moved to the Mohegan Colony in northern Westchester County in 1924. That is where my mother was born.

Most of this I already knew and had documented before I saw the A-file, but I was unaware of some of it, such as the stint in Noyac (near Sag Harbor). I also did not know the name of the ship that he had first taken to America, and never would have known it if not for the A-file, because he traveled under the name John Flynn. The oral history that I had from both my mother and uncle was that he traveled under the name Jack Knight or Jack Knife. These names were not close enough to allow me to search for him using the index of passenger lists (I did try using those names, without success). As for using his real name, William Stevens, without knowing a specific date or ship, I would have had to look at literally dozens of ship manifests to eliminate potential candidates. I also did not know how many times he had traveled.

The A-File solved all of that, with a complete description of each arrival and why he had traveled. A total of five arrivals were found. The last three arrivals are the key to the whole file, as they occurred after 1 July 1924 when immigration was limited by quotas and immigrants were required to establish permanent legal residence. William Stevens had entered the U.S. prior to 1924, but he did not know the law and so when re-entering the country he tried to get around paying a head tax by claiming to be in transit to Canada instead of admitting to being a permanent U.S. resident. Most of his A-File of 77 pages consists of documents generated between 1946 and 1949 in his attempt to establish that he was a legal permanent resident of the U.S. If he had simply answered a few questions correctly upon each arrival, none of this would have been necessary.

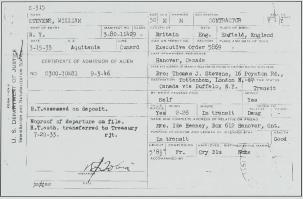

Fast forward to 1946. William Stevens now is widowed and has two adult children by his common-law late wife. He decides to visit friends in England (at the Whiteway Colony). This requires him to get permission from the INS to return to America when his trip is finished. However, when he requests a re-entry permit, the INS informs him that he is not a legal permanent resident. He files an “Application for Registry of an Alien,” form N-105, and the file begins to grow. Earlier, when the Second World War was looming, he had filed an “Alien Registration form” (AR-2) as required at the time (see below). The INS had already started documenting his history with the ship manifests (passenger arrival lists) of his three post-July 1924 crossings. These searches produced S-315 (form I-404-A) Ship Manifest Transcripts (see illustration next page).

The I-404-A forms simplified finding the references to William Stevens on the ship manifests, as the exact line, page and volume are listed, in that order, e.g. “3-80-11429.”[5] Everything that is on the manifest is on this form, plus other information needed by the INS in its investigation. In this case, it states that the Head Tax Authority had not received evidence of a departure for the “in transit” applicant, and so after the maximum time allowed by law the Authority forwarded the head tax to the U.S. Treasurer on 20 July 1933.

The two earlier arrivals pre-dating the 1924 quota legislation are also found on the N-105 form previously mentioned. This form is where William Stevens first explains to the INS his history here in the United States. This form is a four-page document asking 26 questions, some being multi-part, including:

1. Name given at birth

2. Name used when entering the U.S.

3. Occupation

4. Race

5. Last residence before entering the U.S.

6. Date and port of first arrival

7. Name of Vessel

8. Whether or not inspected by an immigrant inspector

9. Place and date of birth

10. Destination

11. U.S. contact upon arrival

12. Whether temporary or permanent status intended

13. With whom did you arrive

14. Present name

15. Present residence

16. Present occupation

17. Personal description, including; height, complexion, eye color, hair color and visible distinctive marks

18. Nationality

19. Sex

20. Whether registered in 1940 and if so, Alien Registration Receipt Card #

21. Whether registrant has applied before

22. Whether registrant has filed a declaration of intention

23. Marital status; if married, name of spouse and date and place of marriage

24. If married, date and place of spouse’s birth, arrival date, residence and naturalization data, including certificate number

25. List of children with ages, places of birth, and current residence

26. Applicant’s residence history since arrival

27. List of employers since arrival

28. List of departures since first arrival and return dates and whether or not inspected each time

29. Whether ever deported or barred from entry to the U.S.

30. Whether opposed to government

31. Whether ever arrested

32. List of evidence showing continuous residence since first arrival

These are followed by the applicant’s signature, and on page 4 the applicant signs again after swearing that changes to the application reflect the true nature of his testimony.

In this example I was afforded information about my grandfather’s first marriage that I could have found no other way. It gave his first wife’s full name, and the month, year, and place of their marriage. Inasmuch as I did not know her full name, I would have had to order all the marriages for several years for men named William Stevens, from the Public Record Office in London. At £6 per certificate this could get expensive fast.

Another part of the oral history that was only partly right concerned the daughter from his first marriage. Her name was Ida Winifred Stevens and she was born 1 December 1904.[6] She married Herbert Henney sometime before 1928 and had a son later that year. In my family, the name Henney (also Heaney) was believed to have been Penney. I spent ten years looking for Ida Penney and her son all over Canada (specifically in Nova Scotia, where my uncle believed they lived). Since they were really named Henney and every other person in Nova Scotia seemed to be named Penney, I had little chance of actually finding them. The ship manifests[7] located through the A-File gave the correct information including the correct place of residence (Hanover, Ontario). That led me, through other means[8] to the name of her late husband, the exact date and place of birth and baptism of her son, and her husband’s death and place of burial.

ship manifest transcript

Most of the rest of the file contains exhibits collected by William Stevens to prove that he had not relinquished residence. They are dated materials such as automobile registrations, driver’s licenses, envelopes, and a bankbook. This last item is interesting as it begins in November 1924 and ends in 1931 after the stock market crash. It shows an entry the day my mother was born, presumably a withdrawal to pay for the hospital costs.

The list of auto registrations is a history of the vehicles that he owned from 1919 through 1938. Also each of these items dates his residence in one of three places, so that I am able to pinpoint fairly closely, within a few months or even weeks, when a move was made from one residence to another.

This leads to another bit of oral history. In the winter before America entered World War II, William Stevens worked as a carpenter helping to build Fort Dix, New Jersey. Among his personal papers, my grandfather had left behind a list of paychecks he had received during this period. It turns out that he lived in Trenton at the time and also worked for a man named S. Sherman, driving a bus. The address where he lived during this period is given in the form of an address report card in 1940. Now I can go to that address and see the building where he lived (if it still exists).

The file also contains references to friends and family. Two of the documents are “Affidavits of Witness in Registry Process.” While they contain mostly corroborative testimony on information already known, in the instance of Bern Dibner, a brother-in-law of William Stevens, I learned that he also lived on Long Island in the early 1920s, a fact that may help his family in tracing his whereabouts before he married my grandmother’s sister.

There is a receipt from a business that William Stevens used for many years, and two letters from the same business in testimony of his character. It seems that the first letter failed to mention the financial arrangements he had with them, which showed his ties to the community. The second letter rectified that oversight. Also there is a Western Union Telegraphic Money Order Receipt, establishing his location on a given day, during one of his trips to Ontario. Also a letter from the Mohegan Colony documents his five-year employment by them from 1928 through 1932.

The Alien Registration Form (AR-2) was required by all aliens beginning in August of 1940 and duplicates much of what was found in the previously mentioned Application for Registry of an Alien. The AR-2 is, however, more likely to be found in most A-files and thus should be discussed here. There are a few differences. For instance, for “name” it does not ask “at birth,” just present name. Under physical description it does not ask for distinctive marks (like the tattoo on his right forearm), but does include weight. Instead of first arrival, it asks for the most recent arrival. For occupation it asks both present occupation and usual occupation, a poignant reminder of the effects of the Depression. The single most important difference in this case was the inclusion of the question about military service. This form confirmed that William Stevens had been in the British Royal Navy from 1897 to 1899, which coincides with the oral history of his joining at age 14 (his birthday was in September) and remaining just three years to age 17. Finally, the form includes his fingerprint and his signature, which many of the other documents duplicate.

For me, obtaining this A-file was rather easy. I was fortunate to have his alien registration number from his unused reentry permit. I filed my request on 9 December 1999, and received the file 1 April 2000. However, it is generally suggested by Marian L. Smith, Historian at the Department of Justice, that numbers found from indexes (such as CR numbers among the soundex cards) not be used, as this can lead to incomplete searches at the INS. At the time I made my request, files smaller then 100 pages were generally sent free of charge. This policy may change if it has not already. It is still recommended that you always ask for all documents unless you are sure of just what you want. You never know what you might find in a file at the INS.

There is a follow-up to this story. A friend at the Jewish Genealogical Society meeting in New York last December recommended the web site www.anybirthday. com. I tried the site out by typing in the name of my cousin, the son of the Ida Henney mentioned above. I had his date of birth and when the list of Henneys came up, I saw his birthday, and I got his zipcode. Another website (I used Yahoo) led me to his address and phone number. My mother called him and they spoke for nearly an hour. He grew up here in New York City. All that time he had no idea he had family living so close by. He did not even know any of my family existed. This made Christmas 2001 a very special one for all of us. (I have not used his name here so as not to violate his family’s privacy.)

The Colonies Associated with William Stevens

Finally, I want to mention a little about the colonies that William Stevens lived in during various times in his life.

William Stevens was involved for most of his adult life with several colonies, each of which had its own history and purpose. These colonies included first the Whiteway Colony near Stroud, Gloucestershire, England; then the Stelton Colony in Piscataway, Middlesex County, New Jersey; and finally the Mohegan Colony in Westchester County, New York. These colonies were part of a phenomenon of experimental communities in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The Whiteway Colony was an offshoot of the Purleigh Colony in England. It was originally based in part on the teachings of Leo Tolstoy, emphasizing freedom, equality, self-government and brotherhood. Many of the colonists had a strong distrust of government and many were conscientious objectors during the First World War. Whiteway had another interesting characteristic involving landholding. The belief was that anyone should hold land who was willing to use it productively and for the good of the community. The colony was started by a small group that purchased forty acres from a large estate that was being divided at the time (about 1898). The principal took the deed, skewered it with a pitchfork, and burned it. This was meant to prevent the land from ever being sold. The members then decided who was to use what land, so as to make the land most productive. That meant that some of the land was farmed in common, to raise crops for the colony. Each did his/her own thing. One man started a bakery, first to supply the colony and later, as the operation gained renown, to raise cash in the open market.

Followers of the Ferrer School of thought started the Stelton Colony. They were anarchist and libertarian New York intellectuals, many of eastern European origin, who wanted to create a “modern” school in the tradition of Spanish anarchist Francisco Ferrer (1859-1909).

The Mohegan Colony was an offshoot of the Stelton Colony. It included a Ferrer-type school and also several other amenities, such as tennis courts and a lake for recreation. Property could be purchased from the colony at a reasonable price and the deeds to that property required the owner to pay an annual fee to support the common grounds and activities. There were quite a few people at the colony living in interfaith and interracial marriages and others that did not believe in formal marriage. It became a social oasis for people living on the fringe of society’s social norms.

It was not uncommon for members of one colony to migrate to another. William Stevens was not the only member to make such moves.

The Mohegan Colony celebrated its 75th anniversary several years ago and the Whiteway Colony celebrated its centennial. There are several books that shed light on these colonies and their inhabitants, which better illustrate just what they were about. Among them are, Whiteway Colony; the Social History of a Tolstoyan Community, by Joy Thacker (1993), and Anarchist Voices; An Oral History of Anarchism in America, by Paul Avrich (1995).

These colonies do have some records of their activities and who their members were at various times. For those who have oral history about members of their family participating in these experimental communities, it may be worth writing to them for more information. Rutgers University has a “Modern School Collection” among its Manuscript Collection, which includes material from the Mohegan and Stelton Colonies, among others.

Notes

[1] Evidence of William Stevens’ birth includes his civil registration and his Social Security Form SS-5.

[2] National Archives microfilm T715, vol. 5954, pp. 152/154 (numbers in upper right hand corner).

[3] 1920 Census, Piscataway, Middlesex Co., N.J., e.d. 55, sheet 24B.

[4] N.Y.C. Dept. of Health Marriage Certificate, Bronx 1908 #439; also City Clerk’s Marriage License, Bronx #7397.

[5] Line 3, page 80, volume 11429 represents William Stevens’ entry on the Ship Manifest of the S.S. Aquitania, which arrived at the Port of New York on 15 March 1933.

[6] GRO England, Entry of Birth, W. Ham, #194 (December Qtr.).

[7] Ship Manifest of S.S. Aquitania, note 5, above.

[8] Those details came from St. James’ Anglican Church in Hanover, Ontario.

by Arthur J. Simpson III

Originally published in The NYG&B Newsletter, Spring/Summer 2002

© 2011 The New York Genealogical and Biographical Society

All rights reserved.